Key Points

Estate tax rates were lowered and exemptions raised dramatically in the 21st century with the result that married couples can potentially pass on an estate of up to $10,980,000 with no tax liability.

President Trump’s proposal to eliminate the estate tax while taxing capital gains at death could, in theory, raise a comparable amount of tax revenue as the current estate tax, if his proposed exemption allowance is lowered.

More research is needed to measure the impact of estate taxes and reforms to estate taxes on economic efficiency, behavior and the distribution of wealth.

U.S. Capital Gains and Estate Taxation: A Status Report and Directions for a Reform

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series of tax-related articles sponsored by the Penn Wharton Budget Model and the Robert D. Burch Center at Berkeley. All of the articles in this series are forthcoming in a book by Oxford University Press, co-edited by Alan Auerbach and Kent Smetters.

U.S. Capital Gains and Estate Taxation examines the economic consequences of estate taxes and their interaction with capital gains taxes. Wojciech Kopczuk (2016) finds that allowing people to pass on an asset with unrealized capital gains at death creates an incentive to avoid realizing capital gains while alive. The author then compares the revenue consequences of taxing capital gains at death with the current estate tax.

The Estate Tax

The U.S. estate tax originated in 1916 with the current structure in place since 1976. Figure 1 shows that estate tax rates and exemptions have changed in the 21st century. For example, in 2001, estates over $675,000 were subject to estate tax with the tax rate reaching 55 percent at $3 million. Starting in 2013, the top estate tax rate is 40 percent and the size of estates subject to this tax is adjusted for inflation. In 2017, estates over $5,490,000 are subject to estate tax. Federal revenues from estate tax were more than $5 billion lower in 2014 than in 2001. In 2014, estate taxes made up under one percent of federal government revenue.

Figure 1: Top Tax Rate and Exemption

Source: Kopczuk (2016)

Estates pass free of tax to a surviving spouse. Since 2011, any unused exclusion (e.g. the approximately $5.5 million that can be passed on tax free) can also be passed to a surviving spouse. The ability to pass unused exclusions to surviving spouses means that, in 2017, the surviving spouse of a married couple can pass on an estate worth up to $10,980,000 before that estate is subject to tax. In addition, various kinds of trusts can also be used to reduce tax liability when estates are passed on.

Basis Step-up at Death

However, the existing estate tax code also has a feature called “step up in basis at death” that reduces tax liabilities. When a person passes on an asset that increased in value since it was bought, that asset is not subject to the normal capital gains tax that would otherwise be paid if that asset were sold instead of bequeathed. Instead, “basis step-up” is applied and the asset is passed on at the market value at the time of death. When heirs eventually sell the inherited assets, they only pay capital gains tax on the difference between the value when inherited and the sale price. Thus, it is possible to avoid paying capital gains tax on asset appreciation during a person’s lifetime.

The Economic Impact of Estate Taxes

Estate taxes might affect the aggregate capital stock. The impact depends on why people leave assets to their heirs. Bequests may be on purpose or accidental, the result of precautionary saving that is no longer needed. If bequests are purposeful, an estate tax may reduce saving by people whose estates are subject to tax. However, Kopczuk (2016) surveys the empirical literature and finds that the effect of estate taxes on the size of estates is small. This result suggests that many bequests might be accidental, which are less likely to be impacted by the estate tax.

Kopczuk (2016) argues basis step-up at death also distorts economic decisions. First, older people are incented to retain assets whose value went up and to sell assets whose value went down, leading to an inefficient allocation of capital. Second, people may engage in costly methods to access assets without realizing capital gains, such as loans where the assets are used as collateral. Third, basis step-up might distort saving decisions. Finally, basis step-up may disincentivize gifts, which do not benefit from stepped-up basis.

Estate Tax Reform Proposals

Kopczuk (2016) also investigates the potential impact of different reforms to estate taxation. One possible reform is to tax capital gains at death and use the new revenue to reduce or repeal estate taxes. During the 2016 presidential campaign, for example, President Trump endorsed taxing capital gains at death while eliminating the estate tax. In theory this reform could simplify the tax system and reduce the incentive to hold unrealized capital gains.

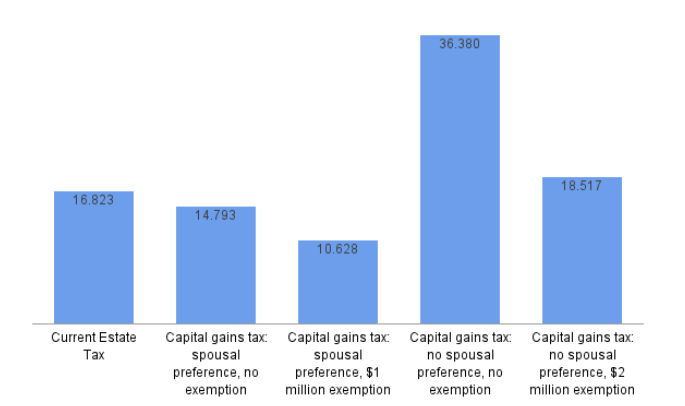

Kopczuk (2016) uses the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances to estimate the potential impact of eliminating the estate tax and instead taxing capital gains at death. Figure 2 shows the revenue generated by the current estate tax as well as different ways of taxing capital gains at death without an estate tax.

Figure 2 shows that the current estate tax raises about $16.8 billion. A capital gains tax with a spousal preference (where assets can be passed to a spouse tax free) and no exemption will produce about $2 billion less revenue than the current estate tax. However, even small estates would be subject to a capital gains tax at death, meaning that they will actually owe more taxes than under current law, which exempts smaller estates. Increasing the exemption to $1 million reduces revenue by another $4 billion. However, removing the spousal benefit and eliminating the exemption raises more than twice the revenue of the current estate tax. A capital gains tax at death that starts after a $2 million exemption and does not have a spousal preference generates roughly $1.7 billion more than the current estate tax. In contrast, the plan endorsed by President Trump during the 2016 campaign, would have a $10 million exemption, likely producing less revenue than any of the options shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Tax Revenue in Billions of Dollars

Source: Kopczuk (2016) based on data from 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances

Kopczuk (2016) also investigates other types of reform, which include requiring heirs to pay capital gains tax based on the value at original purchase, but not until the heirs sell the asset.

Conclusion

The U.S. estate tax has changed in the past two decades and brings in less tax revenue than in the past. Basis step-up creates an incentive for people to avoid realizing capital gains during their lifetimes. One policy alternative is to tax capital gains at death. The amount of tax revenue this reform generates depends on if spouses are allowed to inherit assets tax free as well as the threshold at which the tax begins.

More research is needed on basis step-up. Can basis step-up be a part of an optimal tax system? How many people hold onto unrealized capital gains as part of estate planning? Would higher estate tax rates provide an incentive for people to realize capital gains while living? How do today’s persistent low interest rates impact the economic efficiency of an estate tax? Future research is also needed to measure the impact of estate taxes on the work and saving decisions of heirs.

A discussion of this paper is provided by James M Poterba.