By Austin Herrick

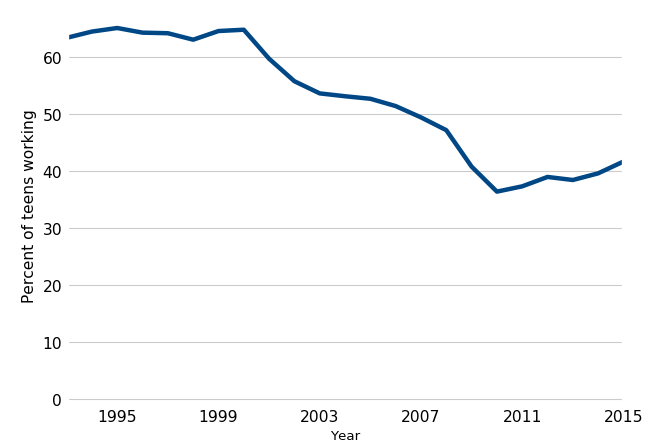

Teenage employment has declined significantly since the late 1990s. Using data from the Current Population Survey, Figure 1 shows that 63 percent of teens aged 16 to 18 worked in 1993, but that percentage fell to 41 by 2015.

Figure 1: Youth Employment in Decline

Figure 1: Youth Employment, Percent Employed

Source: Current Population Survey, 1994-2016

Earlier studies suggest that increased college preparation activity by high school students drove this trend. It’s well known that the college wage premium increased significantly over the last 30 years. This increase may induce more diligent academic preparation by teenagers. If true, we expect to observe a divergence in labor-force participation between teens who prioritize college entry and those who do not.

We find a strong link in U.S. micro-data between parental education and teen employment. As seen in Figure 2, teen employment increases with parents’ education up to a point, but decreases for the teenagers with the most educated parents. The characteristics of teens’ work differs too – 26 percent of working teens whose parents lack high school degrees worked at least 1000 hours per year, compared to just 7 percent of working children of graduate degree holders.

Figure 2: Parental Education Increases Teen Employment - to a Point

Youth Employment by Parental Education, Percent Employed

Note: Highest Level of Education achieved by either parent is used as a tiebreaker. Standard errors shown in black bars.

Source: Current Population Survey, 1996-2015

Financial concerns may play a role here – income from working teens accounts for 11 percent of family wage income in the bottom of the parental education distribution, and only 3 percent at the top. Teens with less educated parents, then, may view teen labor as an important source of family income, highly educated households may view it as preparation for college. If the returns to college continue to increase, these differences in work patterns by the level of parents’ education my grow.

Lower labor participation over time implies changing attitudes toward youth employment. Teens with highly educated parents may have different motives for working than those whose parents have less education. More research into these motivations may provide insights useful for designing effective labor and education policy.