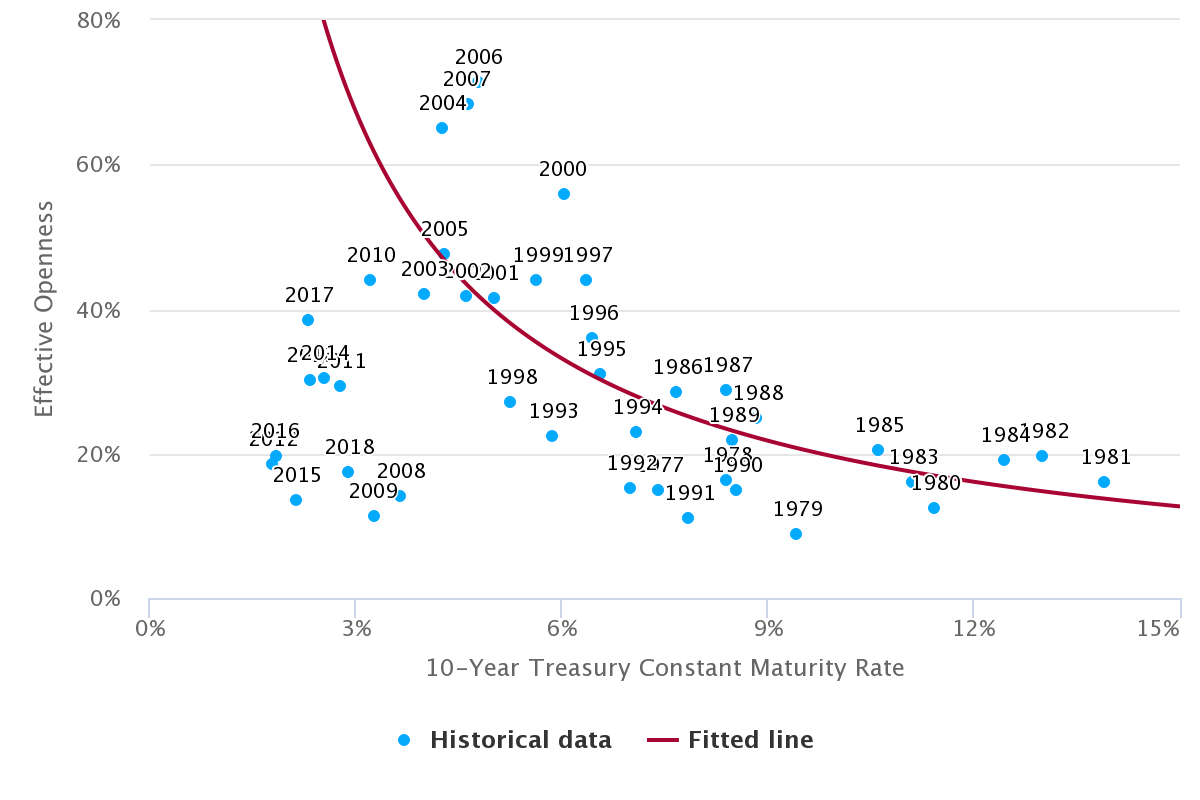

We previously defined a measure of effective openness of the U.S. economy to foreign investment flows. We found that, historically, when tariff rates increase, effective openness is lower. Here, we compare the relationship between effective openness and average interest rates on U.S. government bonds with 10-year maturities.1 Figure 1 displays effective openness and 10-year interest rates in each year.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Treasury Constant Maturity Rate. Available at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/115.

Demand for government debt assets by all market participants influences the market interest rate on that debt. All else equal, more demand increases the price of government debt, which is equivalent to a lower interest rate. We examine the relationship between foreign demand, measured as effective openness, and the interest rate.

We abstract from a number of features of the debt market, including the effect of secular changes in the supply of debt by U.S. fiscal policy and major interventions by the Federal Reserve in credit markets. For example, during the Quantitative Easing interventions by the Fed, the Fed aggressively purchased longer maturity assets from 2009-2014. Even after expanding its balance sheet, the Fed continued to rollover its assets until 2018, when it stopped purchasing new bonds as older issues matured.

The fitted line in Figure 1 shows the estimated relationship between effective openness and interest rates on 10-year Treasury debt:2

As the effective openness of the economy increases, interest rates decline. This correlation is consistent with the finding in Warnock and Warnock (2009) that foreign purchases of U.S. government bonds have a significant inverse relationship to long-term interest rates.3

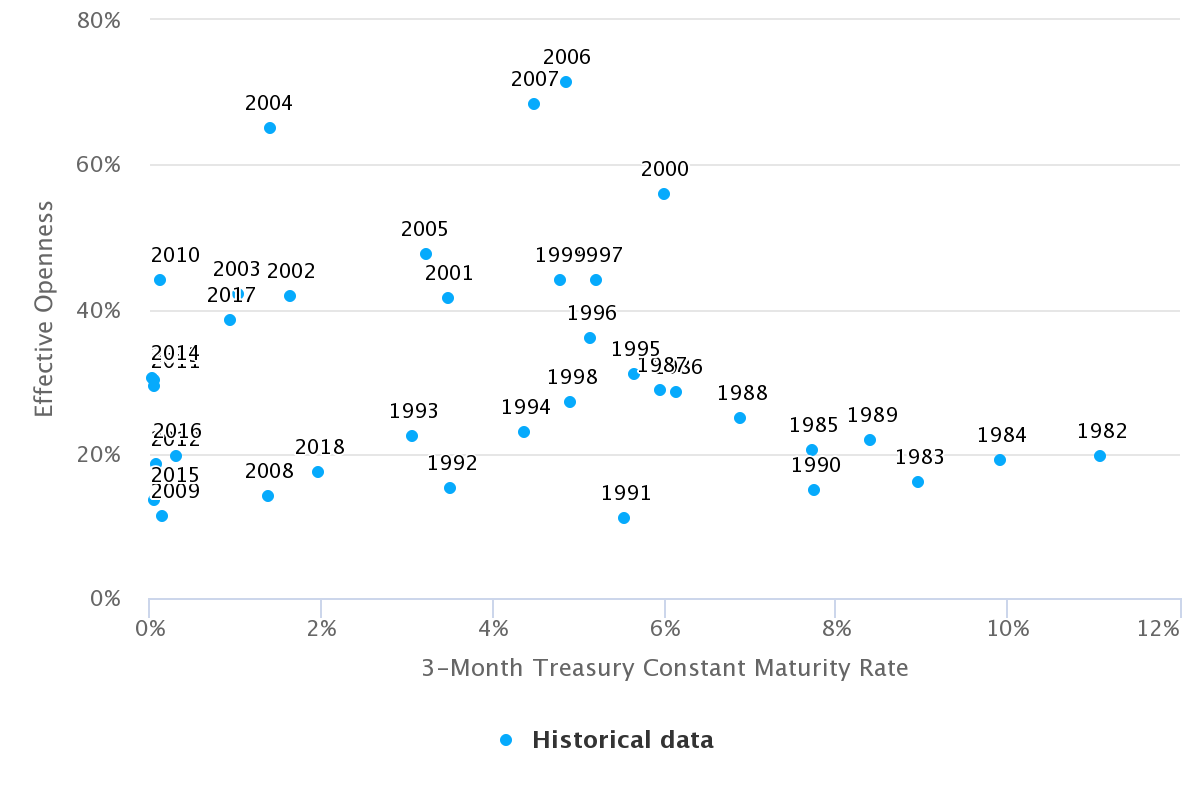

While there appears to be a connection between 10-year rates and effective openness, the relationship between effective openness and short-term rates is less clear. If short-term rates are almost entirely set by policy, we expect effective openness to have little effect on them. In addition, we do not expect a strong relationship because foreign demand for long-term Treasury debt is usually higher than demand for short-term debt.4 Figure 2 displays effective openness and interest rate on 3-month U.S. Treasurys in each year. We find that effective openness and short-term interest rates do not appear to be related unless we exclude periods of easing5 (that is, lowering of the federal funds rate).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Treasury Constant Maturity Rate. Available at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/115.

Our basic empirical analysis of effective openness and federal debt interest rates shows that foreign asset demand has an inverse relationship with long-term interest rates. We previously found an inverse relationship between tariff rates and openness. Thus, in a trade-war scenario, we expect higher interest rates on federal debt, unless the Fed steps in. Higher interest payments on government debt would generate a worse outcome for the U.S. economy, and would, for example, increase the dynamic cost that we previously estimated for the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

-

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Treasury Constant Maturity Rate. Available at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/115. ↩

-

Our nonlinear regression model takes the form of 1/x with an R-squared measure of 0.41. ↩

-

Warnock, F. and Warnock. V (2009), “International capital flows and U.S. interest rates,” Journal of International Money and Finance, vol. 28, pp. 903-919. ↩

-

U.S. Department of the Treasury. U.S. liabilities to foreigners re U.S. Securities. Available at: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Pages/shlreports.aspx. ↩

-

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Effective Federal Funds Rate. Available at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS. ↩

Year,Effective Openness,10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate

1977,14.882520,7.417631

1978,16.344530,8.408387

1979,8.789809,9.432943

1980,12.553840,11.433440

1981,16.193010,13.921370

1982,19.704980,13.005500

1983,16.120740,11.103000

1984,19.137510,12.458110

1985,20.501090,10.619800

1986,28.616640,7.672840

1987,28.889670,8.392680

1988,24.862590,8.848000

1989,21.790340,8.493720

1990,14.841640,8.552400

1991,11.100410,7.862440

1992,15.263670,7.008845

1993,22.465090,5.866280

1994,23.016010,7.085181

1995,31.036090,6.573920

1996,35.924610,6.443532

1997,44.068480,6.353960

1998,27.172660,5.262880

1999,44.060410,5.646135

2000,55.888970,6.030279

2001,41.533860,5.020686

2002,41.693580,4.613080

2003,42.058710,4.013880

2004,64.979290,4.271320

2005,47.567840,4.288880

2006,71.357430,4.795000

2007,68.243290,4.634661

2008,14.241000,3.664263

2009,11.295330,3.264120

2010,43.957350,3.215060

2011,29.346550,2.781640

2012,18.423290,1.803440

2013,30.182090,2.350160

2014,30.390370,2.539560

2015,13.559910,2.138287

2016,19.792030,1.837440

2017,38.488070,2.329480

2018,17.416940,2.911245

Year,Effective Openness,3-Month Treasury Constant Maturity Rate

1982,19.70498000,11.08992000

1983,16.12074000,8.95132000

1984,19.13751000,9.91855400

1985,20.50109000,7.72383100

1986,28.61664000,6.14636000

1987,28.88967000,5.96488000

1988,24.86259000,6.88592000

1989,21.79034000,8.39456000

1990,14.84164000,7.74648000

1991,11.10041000,5.53960000

1992,15.26367000,3.51434300

1993,22.46509000,3.06600000

1994,23.01601000,4.37249000

1995,31.03609000,5.66036000

1996,35.92461000,5.14559500

1997,44.06848000,5.20144000

1998,27.17266000,4.90696000

1999,44.06041000,4.77760900

2000,55.88897000,5.99992000

2001,41.53386000,3.47866900

2002,41.69358000,1.63532000

2003,42.05871000,1.02804000

2004,64.97929000,1.39872000

2005,47.56784000,3.21612000

2006,71.35743000,4.85156000

2007,68.24329000,4.48095600

2008,14.24100000,1.39685300

2009,11.29533000,0.15092000

2010,43.95735000,0.13844620

2011,29.34655000,0.05284000

2012,18.42329000,0.08760000

2013,30.18209000,0.05708000

2014,30.39037000,0.03272000

2015,13.55991000,0.05251000

2016,19.79203000,0.31936000

2017,38.48807000,0.94896000

2018,17.41694000,1.97168700